Immunomodulators in warts: Undiscovered or ineffective?

Surabhi Sinha , Vineet Rehan , 1ve Vijay K Garg 1 Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Abstract

Cutaneous warts are known to be recurrent and often resistant to treatment. Resistant warts may reflect localized or systemic cell-mediated immune (CMI) deficiency against HPV. Various treatment methods are available; most treatments applied by the provider, such as cryotherapy, chemical cauterization, curettage, electrocautery, and laser ablation, are destructive and lead to scarring. Many agents applied to the patient, like podophyllotoxin, carry the risk of site reactions and recurrence. Therefore, immunotherapy is a promising modality that can lead to wart healing without causing any physical changes or scarring and can also enhance host response against the causal agent, thereby leading to complete healing and reduction in recurrences. Immunomodulators can be administered systemically, intralesionally, intradermally, and topically. Several agents, such as cimetidine and interferons, have been extensively tried and studied; others, like echinacea, green tea catechins, and quadrivalent HPV vaccine, are relatively new and their effectiveness has not yet been fully determined. While some, like levamisole, have shown no efficacy as monotherapy and are now used only in combination, large and long-term, randomized, placebo-controlled trials are needed for newer agents to clearly demonstrate their effectiveness or lack thereof. This review will focus on immunomodulators used in wart treatment and studies related to them.

Keywords: cimetidine, imiquimod, immunomodulator, levamisole, resistant, warts

What was known?

Immunotherapy is a promising modality for recurrent and/or resistant warts, leading to healing without causing any physical changes or scarring and enhancing host response against the causal agent, thereby resulting in complete healing and reduced recurrences.

Immunomodulators can be administered systemically, intralesionally, intradermally, and topically.

Some agents such as cimetidine, levamisole, and zinc have been studied in several randomized trials, determining their effectiveness or lack thereof.

Newer immunomodulatory agents are emerging, and studies are needed to clearly define their roles.

Introduction

Cutaneous infections caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) are generally recurrent and among the most troubling conditions for dermatologists. HPV causes numerous infectious lesions, with common warts being the most prevalent. Warts typically self-limit, but spontaneous resolution can take months to years. Spontaneous clearance rates are also notoriously low (23% at 2 months, 30% at 3 months, and 65-78% at 2 years), underscoring the need for intervention. Even after complete removal, they can recur, making them extremely frustrating for both patients and physicians. Stubborn warts may reflect localized or systemic cell-mediated immune (CMI) deficiency against HPV. Various reasons have been proposed, such as the absence of memory T cells targeting HPV infection, failure of lymphocytes to undergo sufficient clonal expansion upon stimulation, inability of T lymphocytes to migrate to infection sites, and weak effector response mechanisms. As a result, warts are particularly exuberant in individuals with Hodgkin’s disease, AIDS, and those using immunosuppressive drugs.

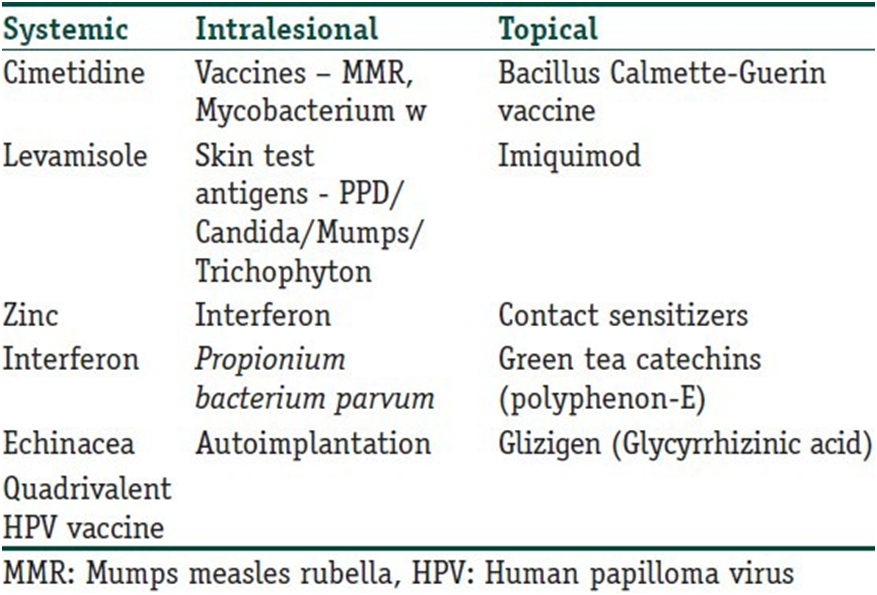

Genital warts pose an even greater problem for dermatologists, primarily due to patients’ reluctance to seek medical attention and their tendency to recur. Recurrent individuals suffer from significant psychological morbidity. Therefore, drugs with immune-stimulating properties are potentially beneficial in these cases. Various treatment methods are available; most treatments applied by the provider, such as cryotherapy, chemical cauterization, curettage, electrocautery, and laser ablation, are destructive and lead to scarring. Many agents applied to the patient, like podophyllotoxin, carry the risk of site reactions and recurrence. Due to the possible presence of some microbial organisms after the physical destruction of visible lesions, recurrence rates are also high. Cryotherapy, for example, has been reported to have wart recurrence rates of up to 30%, possibly due to the lack of an immune response. Therefore, immunotherapy is a potentially logical method that can lead to healing without causing any physical changes or scarring and can enhance the host response against the causal agent, thereby leading to complete resolution and reduced recurrences. Despite the many immunomodulators that have been tried, none have been found ideal due to insufficient sample sizes in studies, practicality of use, side effects, or limited efficacy. Therefore, the search for the ideal drug is still ongoing! Table 1 lists various agents that have been tried as immunomodulators in the treatment of warts. However, the treating physician should remember that none of the treatments discussed in the review are FDA-approved for wart treatment (except Polyphenon – E).

Table 1

Various immunomodulatory agents used in the treatment of warts

Systemic Agents

H2 antagonists (evidence strength D, I)

It is believed that H2 receptor antagonists have immunomodulatory properties, but clinically significant effects have only been documented for cimetidine and ranitidine. Karaman et al. [7] At high doses (25-40 mg/kg/day), cimetidine stimulates IL-12 and reduces IL-10, leading to an increase in Th1 response and suppression of Th2 cells. [4, 8, 9] It also increases IL-2 production, thereby stimulating lymphocyte proliferation and enhancing CMI. It prevents histamine-induced stimulation of T suppressor cells. [5, 6]

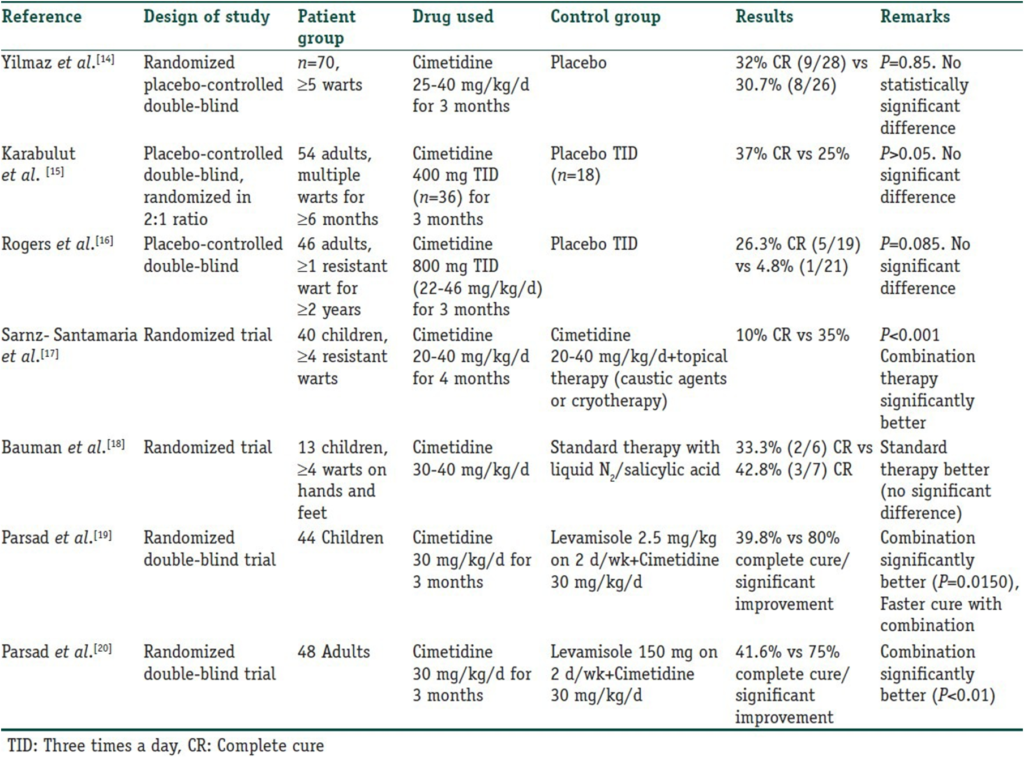

Cimetidine has been used in various trials for warts. Four open-label studies were conducted, reporting a complete response (CR) rate ranging from 48.8% to an impressive 81.8%, which did not support such high clearance rates and showed rather disappointing results.

Table 2

Randomized controlled trials for cimetidine in the treatment of verruca vulgaris

It has also been used in HSV infections, herpes zoster virus (HZV) in immunocompromised individuals, mucocutaneous candidiasis, and common variable immunodeficiency disease (CVID). Dohil et al. treated 13 children with Molluscum Contagiosum with cimetidine at 40 mg/kg/day. Nine of them were completely cleared while one showed partial clearance. Facial MC lesions responded faster than body lesions.

Side effects include headache, dizziness, diarrhea, rash, urticaria, hair loss, gynecomastia, breast pain, arthralgia, and myalgia. In an open-label study conducted in adults, it was observed that a higher dose up to 40 mg/kg/day (maximum 3500 mg/day) correlated with an increased response. The FDA-approved maximum dose is 2400 mg/day, so the risk-benefit ratio should be clearly evaluated before higher doses are used. It is not officially approved for children under 16 years old, but it continues to be used.

Levamisole

Levamisole is an immunomodulator used in many patients with common viral infections such as warts and molluscum contagiosum. It alters the polymorphonuclear leukocyte (PMN) chemotactic response. While inhibiting the breakdown of cyclic GMP, it stimulates the phosphodiesterase breakdown of cyclic AMP, which appears to be associated with increased chemotactic response. An increase in adenosine deaminase and a “scavenger” effect on free radicals are also believed to play a role. It stimulates the upregulation of Th1 cells and IL-2, 12, IFN-gamma, and the downregulation of Th2 cells, preferably with a simultaneous effect on IL-4,5,10, involving delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH), with a dose of 2.5 mg/kg two to three times a week.

Although it shows promise in combination with cimetidine for wart treatment, monotherapy did not demonstrate this. A single double-blind, placebo-controlled study by Amer et al. showed a 60% cure rate in 40 patients with warts treated with 5 mg/kg for three consecutive days every two weeks for five months (compared to 5% for placebo), but other randomized trials did not show much efficacy.

The most common side effects are nausea, taste alteration, flushing, hair loss, and flu-like illness. Patients should be monitored for agranulocytosis (<20% PMN), which is rare but potentially fatal initially reversible. Bone marrow is not permanently damaged, and patients with the HLA-B27 genotype are more susceptible. Cases of multifocal leukoencephalopathy have also been described.

Zinc (Evidence level – C, II)

Zinc is perhaps the most important trace element for immune function. Kitamura et al. suggested that zinc homeostasis regulates dendritic cell function through toll-like receptor (TLR) mediated mechanisms. Zinc deficiency has been shown to decrease immunity against skin infections. Additionally, it has specific antiviral activity; firstly, by cross-linking viral DNA double helixes, preventing the necessary division for viral replication, and secondly, by rendering viral surface glycoproteins inactive, thus interfering with penetration into a susceptible host cell.

Zinc sulfate is the compound with the highest bioavailability and best tolerated. Each 100 mg zinc sulfate capsule contains 22.5 mg elemental zinc. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, and mild epigastric discomfort.

A placebo-controlled (PC) trial was conducted for the treatment of resistant warts, using oral zinc sulfate at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day (2.5 mg/kg/day elemental zinc) once daily. Complete clearance was observed in 87% of the treatment group compared to 0% in the placebo group. In another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled (DB PC) study, oral zinc sulfate at a dose of 10 mg/kg/day was given for up to 2 months to patients with recalcitrant warts. Clearance was observed in 76.9% of the treatment group (10/13) and 7.8% of the placebo group (1/13). The regression of warts was not asymptomatic but rather associated with itching, an increase in lesion size and number in the first 2 weeks, followed by resolution. However, Lopez-Garcia et al. conducted a DB PC study in 50 patients with ≥5 resistant warts. They found similar clearance rates with zinc sulfate and placebo (28% vs. 24%) and noted that none of the patients in either group had low initial zinc levels. Stefani et al. conducted a randomized double-blind study in 18 patients comparing zinc sulfate (10 mg/kg/day) and cimetidine (35 mg/kg/day) for resistant warts for 3 months. They found zinc to be more effective than cimetidine.

Zinc has also been found to be beneficial in cutaneous leishmaniasis, recurrent ENL, and common variable immunodeficiency.

Interferons (IFNs)

Interferons (IFNs) are a class of small (15-28 kD) protein and glycoprotein cytokines produced by T cells, fibroblasts, and other cells in response to viral infection and other biological and synthetic stimuli. As a therapeutic agent, IFNs are divided into three main classes (alpha, beta, and gamma) based on their physicochemical properties, cell of origin, induction mode, and antibody reactions.

IFN has been shown to be active against HPV through three mechanisms: Antiviral, antiproliferative, and immunostimulation. IFNs primarily exert their activities by binding to specific membrane receptors on the cell surface and initiating specific intracellular events, including induction of enzymes, suppression of cell proliferation, increased macrophage phagocytosis, and enhanced lymphocytic cytotoxicity for target cells, as well as inhibition of virus replication in virus-infected cells.

Yang et al. conducted a systematic review of 12 randomized controlled trials related to IFN in the treatment of genital warts, involving a total of 1445 patients. Five studies compared systemic IFN with placebo. They found no significant difference in clearance rates between the two groups. They concluded that locally used IFN was more effective for genital warts than systemic IFN. The most commonly reported adverse reaction to systemic IFN is a flu-like syndrome (presence of any two of the following symptoms simultaneously: fever/chills, headache, malaise/fatigue, and myalgia/muscle pain).

Echinacea

Echinacea (purple coneflower) is a member of the Compositae family. The three main species of medicinal importance are E. purpurea, E. augustifolia, and E. pallida. It was initially used primarily for the prevention and treatment of colds and upper respiratory tract infections (URTI). Coeugni and Kuhnast reported a serendipitous finding of reduced recurrence of vaginal candidiasis during a 6-month follow-up period after URTI treatment. Subsequently, it was tried in cutaneous infections. It influences immune function through T-cell activation, increased number and activity of macrophages, production of TNF and IFN-γ, and inhibition of hyaluronidase produced by bacteria and viruses.

Zedan et al. compared Propolis (Bee Propolis®) (Pollen Assiut, Egypt) 500 mg, Echinacea purpurea 600 mg, and placebo in a single oral dose for 3 months or until complete healing in the treatment of plane, plantar, and common warts. They observed a significant difference between Propolis and Echinacea in common and plane warts (P < 0.05 for each) and a significant difference between Propolis and placebo in common and plane warts (P < 0.01 and P < 0.05, respectively). However, there was no significant difference between Echinacea and placebo in the treatment of any type of wart.

Cassano et al. used Echinacea in an oral supplement (OS) formulation for resistant warts. The nutraceutical OS (ImmunoSkin Plus® tablets, Morgan Pharma srl, Vicenza, Italy) consisted of a cocktail of Echinacea augustifolia, Echinacea purpurea, methionine, inulin, probiotics, taurine, vitamins C, A, B3, coenzyme Q10, and zinc gluconate. They divided their patients into two groups: one received conventional standard treatment (CST) alone, and the other received CST plus OS. CST, which consisted of liquid nitrogen cryotherapy or topical 15% salicylic acid + 15% lactic acid, continued until complete remission. OS was prescribed as one tablet daily for 20 days each month, starting with CST and continuing for four consecutive months. The authors observed complete wart remission in 86% of the CST + OS group compared to 54.5% in the CST group (P < 0.001). New wart development was significantly reduced in the CST + OS group (9%) compared to the CST group (25%) (P = 0.004). The absence of OS was also more likely to be associated with treatment failure (37% in the CST group vs. 8% in the CST + OS group) (P < 0.001).

No significant side effects were reported apart from mild allergic reactions.

Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine

The quadrivalent HPV vaccine was first used by Venugopal and Murrell for the treatment of persistent warts in an adult male. Ault suggested that the vaccine might have the potential to provide cross-protection against strains other than HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. It is believed that the cross-protection results from the significant homology of common capsid epitopes and L1 among various HPV types. Subsequently, several more case reports were published documenting the successful use of the vaccine in treating persistent common and plantar warts. The vaccine is administered intramuscularly into the arm at 0 (or 1), 2, and 6 months. No significant side effects have been reported by any authors. Clearly, broader use of the vaccine cannot be recommended unless supported by larger controlled studies, but these findings are certainly encouraging.

Intralesional Agents

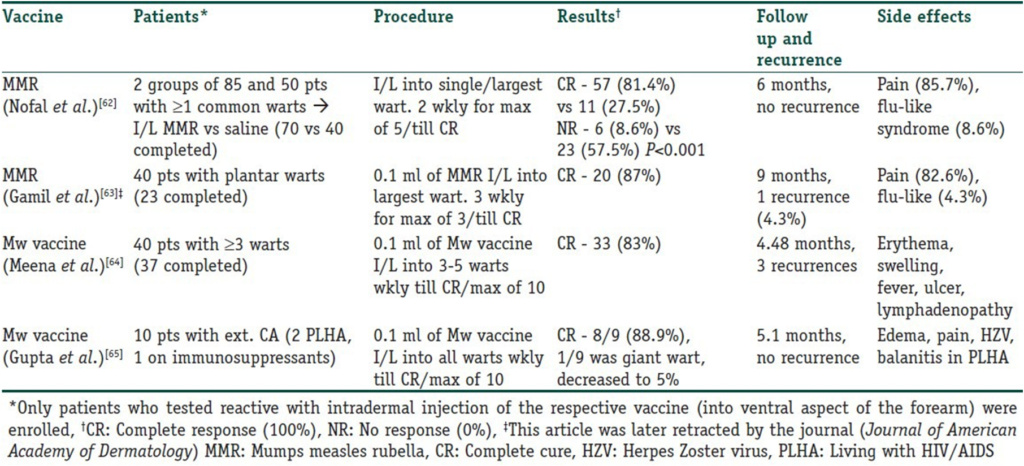

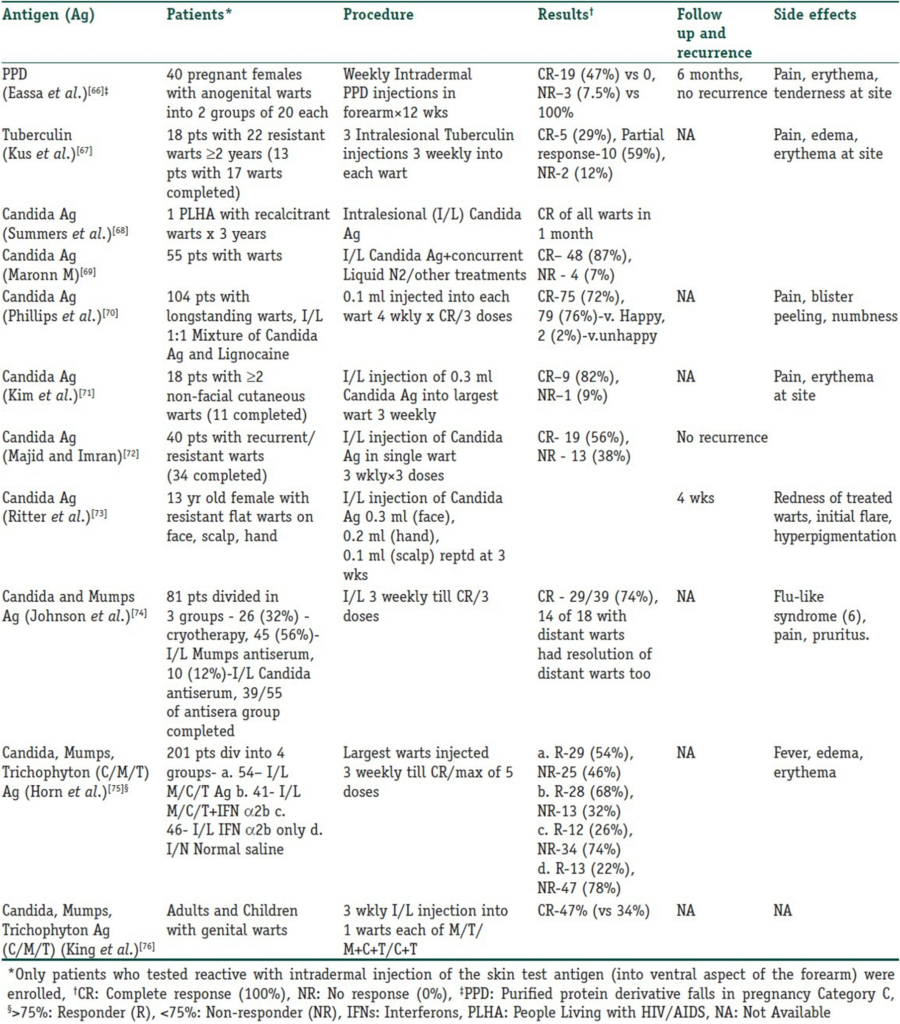

Intralesional immunotherapy utilizes the ability of the immune system to mount a delayed-type hypersensitivity response against various antigens or wart tissue. It leads to the production of Th1 cytokines, which stimulate cytotoxic T cells and natural killer cells to eliminate the HPV infection. Interestingly, this immune response has the potential to resolve not only the primary injected warts but also distant warts. Various authors have used different immunotherapeutic agents for intralesional injection. These include Candida antigen, mumps antigen, MMR vaccine, trichophytin skin test antigen, tuberculin, BCG vaccine, Mycobacterium w vaccine, autologous wart tissue, and injections of IFN-alpha and -gamma. This procedure takes advantage of the high prevalence of immunity to these antigens in the general population. However, this procedure is unsuitable for individuals hypersensitive to any of these antigens, pregnant women, and immunosuppressed persons. The antigens can be injected into normal skin or directly into the wart tissue. In the case of multiple warts, typically the main or first-appearing wart is injected. Tables 3 and 4 detail studies involving vaccines and skin test antigens used in wart immunotherapy.

Table 3

Vaccines used in intralesional immunotherapy for warts

Table 4

Intralesional/Intradermal Skin Test Antigens Used in Immunotherapy for Warts

Intralesional Interferon

The basis of IFN therapy for warts is the observation that a deficiency of T-helper lymphocytes, associated with an inversion of the T4/T8 ratio, is seen in warts, and this deficiency is corrected following IFN therapy.[77] Intralesional IFN-alpha (IFN-α) was tested in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study for persistent genital warts, where the warts were injected twice weekly for up to 8 weeks. Complete clearance was observed in 62% of the IFN group compared to 21% of the placebo group.[78]

Yang et al. reviewed 12 studies on the use of IFN in genital warts, of which 7 used local IFN. The results showed that patients infected with HPV who were given local IFN had a significantly lower recurrence rate compared to those given placebo (relative risk 0.73, 95% CI: 0.63-0.84, p < 0.00001). The results indicated that patients infected with HPV who were given local IFN had a significantly lower recurrence rate compared to those given placebo (relative risk 0.73, 95% CI: 0.63-0.84, p < 0.00001). The results suggest that genital warts, widely accepted as a local disease, are more responsive to local application, which optimizes the suppression of viral replication and cellular proliferation. Additionally, systemic administration of IFN may result in much lower intralesional effects. Intralesional IFN-α has also been successfully used in the treatment of recurrent oral warts in AIDS patients.[79]

Some patients treated with intralesional IFN may experience application site reactions, such as itching, burning sensation, and pain.

Propionibacterium parvum

Propionibacterium parvum, also known as Propionibacterium acnes or Corynebacterium parvum, is a gram-positive, pleomorphic, strictly anaerobic bacterium.[80, 81, 82] It has a strong stimulatory effect on the reticuloendothelial system and has been used in recent years as an adjuvant immunostimulant in chemotherapy for various tumors.[83, 84, 85] It can be administered parenterally or topically.[82, 85] It stimulates the activity of natural killer (NK) cells by inducing the secretion of IFN and TNF.[80]

Nasser conducted a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled (DB PC) trial in 28 volunteers with common warts, of which 20 completed the study. The treatment involved up to a total of five injections. A mild local reaction developed in some warts, indicating the formation of antigen-antibody complexes. They found that in the treatment group, 8 out of 10 volunteers experienced complete clearance of all their warts, 1 volunteer had a reduction in the size and number of warts, and 1 volunteer showed no change. On the other hand, in the placebo group, none except one volunteer showed any changes in their warts (P < 0.001), which was quite significant.

Autoinoculation Therapy

Autoinoculation involves injecting homologous wart tissue into untreated warts, leading to the resolution of both the injected wart and distant lesions. In 2009, Shivakumar and colleagues used homologous autoinoculation to treat multiple palmoplantar and common warts in 60 patients in an open trial.[87] They extracted a portion of wart tissue with an 18G needle and placed it into a subcutaneous notch on the flexor aspect of the left forearm. A total of 73.3% of patients showed complete clearance, with 91% achieving this within the first 2 months. They hypothesized that autoinoculation induced a cell-mediated immune (CMI) response. In 2010, Srivastava and Bajaj also evaluated autoinoculation therapy for warts.[88] However, they excised 3-4 mm of wart tissue with a radiofrequency cutter, crushed it in distilled water, and then injected the fine suspension intramuscularly into the gluteal region. Out of 53 patients, 35 (66%) achieved complete clearance. Despite these impressive results, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have yet to be conducted for autoinoculation therapy.

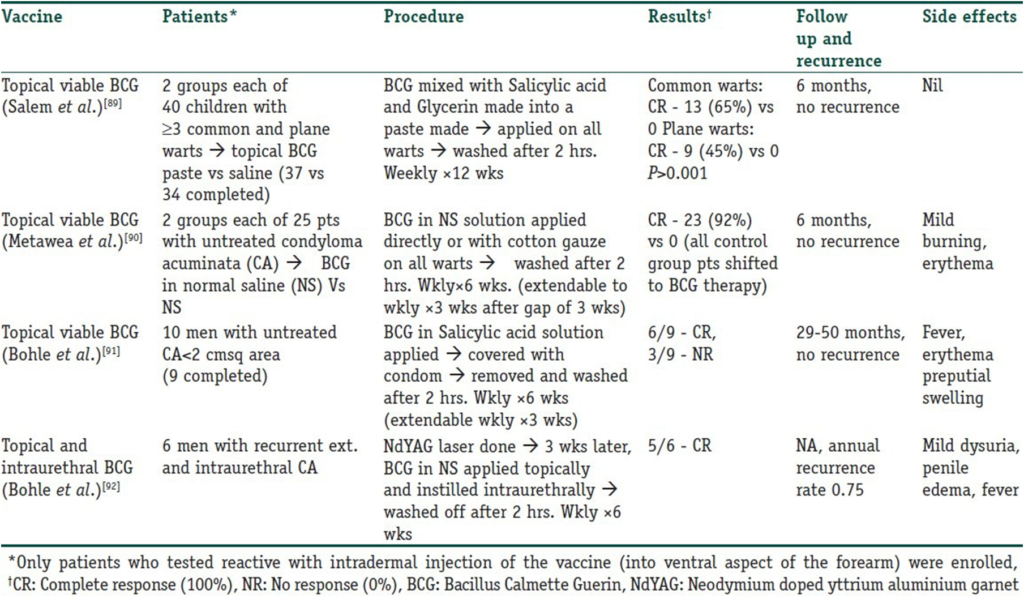

Topical Agents

Immunotherapy for warts can be administered through various methods. The simplest approach involves the topical application of specific inorganic molecules or even immune modulators such as Imiquimod and BCG vaccine, which can elicit a contact hypersensitivity reaction through secondary activation of an immunologic response. Table 5 lists studies conducted with the topical application of the BCG vaccine.

Table 5

Trials using topical BCG vaccine in the immunotherapy of warts

Imiquimod

Imiquimod is an immune modulator that stimulates cytokines such as IFN-α, IL-1,6, TNF-α, GM-CSF, and GCSF . It is FDA-approved in the United States for the treatment of external genital warts. However, its absorption through intact skin is minimal, so it has not been frequently used for cutaneous warts . In an open-label, uncontrolled study, 5% Imiquimod cream was applied five days a week and washed off in the morning . This was continued for up to 16 weeks or until the warts disappeared. Complete clearance occurred in 30% of cases, with a >50% reduction in wart size in 26% of cases. Follow-up at week 32 showed no recurrence in treated areas. The only side effect was mild transient local inflammation. It has also been used for recalcitrant plantar, periungual, and subungual warts .

Contact Sensitizers (Evidence Strength C, IV)

Contact sensitizers trigger a type IV hypersensitivity reaction, making them a form of topical immunotherapy . The three agents used are dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB), squaric acid dibutyl ester (SADBE), and diphencyprone (DCP). DNCB has been shown to be mutagenic and is no longer used. SADBE is costly and less stable in solution compared to DCP; hence, DCP is the preferred compound.

Buckley et al. reviewed recalcitrant palmoplantar warts treated with DCP over 8 years . Patients were sensitized with a 2% DCP solution applied to the inner upper arm every 10-14 days until local erythema and vesiculation occurred. Treatment was repeated up to three times. Resistant warts were then treated with escalating concentrations of DCP: 0.01%, 0.05%, 0.10%, 0.25%, 0.50%, 1.0%, 1.5%, 2.0%, 3.0%, 4.0%, and 6.0%. Treatments were administered every 1-4 weeks. They found that 42/48 patients completed the treatment, showing an 88% clearance rate. However, a large percentage of patients developed side effects, including painful blistering at the sensitization site and near the warts, pompholyx-like or widespread eczematous rash, flu-like symptoms, vesiculation elsewhere due to passive transfer of DCP, and inguinal lymphadenopathy (56%). It was also used for recalcitrant palmar, plantar, and periungual warts .

In another trial, Rampen et al. applied DCP weekly for 8 weeks to 134 patients and achieved a 60% response rate (with 44% complete clearance in 4 months) .

DCP is potentially beneficial as it is less destructive than most ablative methods, less costly, less time-consuming, and can be used for multiple warts simultaneously.

Green Tea Catechins (Polyphenon® E)

Polyphenon® E (MediGene AG, Munich, Germany) is a defined extract of catechins from the green tea leaves of Camellia sinensis, a member of the Theaceae family. It primarily contains tea polyphenols, mainly a group of related flavonoids, especially catechins (over 80%). The lead catechin, (-)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), constitutes 50-72% of the catechin fraction. Green tea catechins are potent antioxidants, and Rösl et al. have shown the inhibition of the transcription of HPV viral proteins by antioxidants. Additionally, inhibition of viral binding to receptors, signal transduction, and cell cycle modification, antiproliferative effects, and the induction of apoptosis by tea catechins may contribute to the pharmacological effect of Polyphenon E ointment. These potential properties support its use in treating warts, especially anogenital warts.

It is a patient-applied modality to be applied three times daily. Mild local symptoms are the most common side effects. Rarely, herpes simplex infection, balanitis, phimosis, and lymphadenitis have been reported. The Food and Drug Administration recently approved Polyphenon E ointment for treating external genital warts in 2006.

Gross et al. conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study comparing 15% ointment and 10% cream formulations to placebo for treating external genital warts. They concluded that the 15% ointment was more effective than the placebo with an acceptable safety profile; however, the 10% cream formulation did not show a statistically significant benefit.

In another trial, Stockfleth et al. found that Polyphenon E 15% and 10% ointments were associated with recurrence rates of 5.9% and 4.1%, respectively, for external genital warts. Other treatment methods have shown recurrence rates ranging from 5% to 65%. For example, cryotherapy demonstrated a convincing clearance rate but had a recurrence risk of approximately 20-40%. Similarly, imiquimod 5% cream and podofilox showed comparable efficacy rates but recurrence rates varied from 13% to 19% and up to 91%, respectively.

Therefore, Polyphenon® E is a promising and relatively safe, self-applied topical treatment with minimal advantages over other self-applied modalities.

Glizigen (Glycyrrhizic Acid)

Glizigen, developed by Catalysis Laboratories, has glycyrrhizic acid as its main ingredient, a substance found in the root of Glycyrrhiza glabra (licorice root). It is known for its anti-inflammatory, anti-ulcerative, and antiviral effects. It inactivates extracellular viruses by interacting with viral proteins, prevents intracellular decapsulation of infectious particles, and disrupts the aggregation capacity of virus particles. Gomez et al. conducted a study to evaluate its use in external genital warts. They combined it with Viusid, an immune-stimulating dietary supplement. They compared Glizigen-Viusid with podophyllin in two groups of 50 patients each. Podophyllin was applied weekly by a doctor for six weeks. Glizigen was self-applied by patients to the lesions according to the surface area: 1-3.9 cm², three times daily; 4-6.9 cm², four times daily; 7-10 cm², five times daily for eight weeks. Patients were also instructed to take 30 ml of Viusid syrup three times a day during the treatment period. They found that 84% of the total patients had lesions <5 cm². Among these, 38 patients in the Glizigen group improved while 5 did not; in the podophyllin group, 36 improved while 10 did not. Thus, Glizigen was slightly better and also better tolerated. However, larger and better-planned studies are needed for more widespread use of Glizigen.

The peak incidence of warts is in children aged 12 to 16 years; therefore, the role of immunotherapy for warts in children needs to be studied in more detail. Systemic drugs like cimetidine had disappointing results in randomized controlled trials, but they continue to be used by some practitioners in children due to ease of administration, lack of pain, and absence of local side effects. Topical sensitizers like SADBE and DPCP have been tried on the face and neck, and imiquimod is extremely suitable for external genital warts in children, as it is painless and effective in this patient population. However, unless topical uses (e.g., topical BCG) prove consistent success in large controlled trials, it is less likely that they will be widely adopted in children due to the associated pain.

Therefore, numerous immunotherapeutic agents have been tried for recurrent warts. Some, like intralesional or intradermal PPD, can be effective, widely accepted, and very cost-effective treatments, especially in countries like India where TB vaccination is routine and mandatory. Immunomodulators have shown effectiveness and lack of major side effects in open studies and small randomized trials. An additional advantage is their potential to prevent recurrences. However, for these agents to be used more widely and routinely, large-scale standardized studies need to be current in the era of evidence-based dermatology.

What’s new?

Many new agents such as echinacea, green tea catechins, and Propionium bacterium parvum have now become available, but there has been little research done on them. However, due to the lack of larger randomized, placebo-controlled studies, a definitive role has not yet been defined.

Most of these agents lack standardization in terms of dosage, mode of application, treatment duration, and interval, underscoring the need for further evaluation.

Spontaneous resolution is a potential confounding factor in all trials involving warts, and therefore, when determining the effectiveness of an agent, open uncontrolled trials are unnecessary.

Footnotes

Source of support: None

Conflict of Interest: None.

Multiple Choice Questions

Maximum approved dose of cimetidine by FDA: 1200 mg/day2400 mg/day3600 mg/day

4800 mg/day

Cimetidine use is not approved for: Children under 4 years oldChildren under 12 years oldChildren under 16 years old

There is no such criterion

Mechanisms of action of levamisole include all exceptPMN chemotactic responseStimulates the breakdown of cyclic AMPIncreases adenosine deaminase levels

Reduces delayed-type hypersensitivity

Dose of levamisole used for immune stimulation:2.5 mg/kg once weekly2.5 mg/kg twice weekly5 mg/kg once weekly

5 mg/kg twice weekly

Reported most common side effect of systemic interferonssyndromeChest painWheezing

Diarrhea

Which of the following is not a mode of action of Echinacea?Activation of B cellsIncrease in macrophage countStimulation of IFN and TNF production

Inhibition of hyaluronidase produced by viruses

Intralesional agents are not recommended for everyone except: Pregnant womenIndividuals with suppressed immunityKnown hypersensitivity to the antigen

Previous exposure to a similar agent

Which of the following statements about imiquimod is incorrect?Stimulates cytokines like IL-1Approved for the treatment of genital wartsGood absorption through intact skin

Used for resistant plantar warts treatment

Contact sensitizers causeI hypersensitivity reactionType II hypersensitivity reactionType III hypersensitivity reaction

Type IV hypersensitivity reaction

One of the following statements about Polyphenon ® E is incorrectfrom tea leavesContains antioxidant substancesAdministered by a physician

Approved by FDA for the treatment of genital warts.

Replies:

1. B

2.Ç

3-DIMENSIONAL

4. B

5. one

6. one

7.D

8.Ç

9.D

10.Ç

References

1. Sterling JC, Handfield-Jones S, Hudson PM. İngiliz Dermatologlar Derneği. Kutanöz siğillerin yönetimi için kılavuzlar. Br J Dermatol. 2001; 144 :4–11. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

2. Scheinfeld N. Molluscum contagiosum tedavisi: Adapalen ile başarılı bir şekilde tedavi edilen bir olgunun kısa bir incelemesi ve tartışılması. Dermatol Çevrimiçi J. 2007; 13:15 . [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

3. Stulberg DL, Hutchinson AG. Molluscum contagiosum ve siğiller. Aile Hekimiyim. 2003; 67 :1233–40. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

4. Elenkov IJ, Webster E, Papanicolaou DA, Fleisher TA, Chrousos GP, Wilder RL. Histamin, insan IL-12’sini güçlü bir şekilde baskılar ve H2 reseptörleri yoluyla IL-10 üretimini uyarır. J İmmunol. 1998; 161 :2586–93. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

5. Gifford RR, Tilberg AF. Histamin tip-2 reseptör antagonisti immün modülasyonu. II. Simetidin ve ranitidin, interlökin-2 üretimini arttırır. Ameliyat. 1987; 102 :242–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

6. Mitsuishi T, Iida K, Kawana S. Viral siğiller için simetidin tedavisi, lezyonlu ciltte IL-2 ve IFN-gamma ifadesini arttırır, ancak IL-18 ifadesini artırmaz. Eur J Dermatol. 2003; 13 :445–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

7. Karaman G, Sendur N, Sevk E. İnatçı siğiller için ranitidin tedavisi: Bir ön çalışma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001; 15 :495–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

8. Rogers CJ, Gibney MD, Siegfried EC, Harrison BR, Glaser DA. Yetişkinlerde inatçı siğiller için simetidin tedavisi: Plasebodan daha mı iyi? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 41 :123–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

9. Mitsuishi T, Iida K, Kawana S. Viral siğiller için simetidin tedavisi, lezyonlu ciltte IL-2 ve IFN-gama ifadesini arttırırken IL-18 ifadesini artırmaz. Eur J Dermatol. 2003; 13 :445–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

10. Cam AT, Solomon BA. Yetişkinlerde inatçı siğiller için simetidin tedavisi. Arch Dermatol. 1996; 132 :680–2. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

11. Orlow SJ, Paller A. Çocuklarda çok sayıda viral siğil için simetidin tedavisi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993; 28 :794–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

12. Gooptu C, Higgins CR, James MP. Viral siğillerin simetidin ile tedavisi: Açık etiketli bir çalışma. Klinik Exp Dermatol. 2000; 25 :183–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

13. Fischer G, Rogers M. Çocuklarda siğiller için simetidin tedavisi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37 :289–90. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

14. Yılmaz E, Alpsoy E, Başaran E. Siğiller için simetidin tedavisi: Plasebo kontrollü çift kör bir çalışma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996; 34 :1005–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

15. Karabulut AA, Şahin S, Ekşioğlu M. Simetidin genital olmayan siğiller için etkili midir: Çift kör, plasebo kontrollü bir çalışma. Arch Dermatol. 1997; 133 :533–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

16. Rogers CJ, Gibney MD, Siegfried EC, Harrison BR, Glaser DA. Yetişkinlerde inatçı siğiller için simetidin tedavisi: Plasebodan daha mı iyi? J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999; 41 :123–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

17. Sáenz-Santamaria MC, Gilaberte Y. Simetidin ve siğiller. Arch Dermatol. 1997; 133 :530–1. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

18. Bauman C, Francis JS, Vanderhooft S, Sybert Başkan Yardımcısı. Çocuklarda çoklu viral siğiller için simetidin tedavisi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996; 35 :271–2. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

19. Parsad D, Pandhi R, Juneja A, Negi KS. Çocuklarda inatçı siğiller için tek başına simetidine karşı simetidin ve levamisol. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001; 18 :349–52. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

20. Parsad D, Saini R, Negi KS. Dirençli siğillerin tedavisinde simetidin ve levamisol kombinasyonunun tek başına simetidin ile karşılaştırılması. Avustralya J Dermatol. 1999; 40 :93–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

21. Cohen PR, Kurzrock R. Herpes simpleks virüs enfeksiyonları ve simetidin tedavisi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988; 19 :762–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

22. Kurzrock R, Auber M, Mavligit GM. Bağışıklığı baskılanmış hastalarda herpes simpleks viral enfeksiyonlarının simetidin tedavisi. Klinik Exp Dermatol. 1987; 12 :326–31. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

23. Truhan AP, Raab B. Simetidin ve tekrarlayan genital herpes. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985; 13 :313–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

24. Mavligit GM, Talpaz M. Herpes zoster için simetidin. N İngilizce J Med. 1984; 310 :318–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

25. Jorizzo JL, Sams WM, Jr, Jegasothy BV, Olansky AJ. Bir immünomodülatör olarak simetidin: Bir model olarak kronik mukokutanöz kandidiyazis. Anne Intern Med. 1980; 92 :192–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

26. White WB, Ballow M. Ortak değişken hipogammaglobulinemisi olan hastalarda simetidin ile baskılayıcı hücre aktivitesinin modülasyonu. N İngilizce J Med. 1985; 312 :198–202. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

27. Segal R, Dayan M, Epstein N, Zecler E, Peller S, Michalevitch R, et al. Ortak değişken immün yetmezlik: Bir aile çalışması ve simetidin ile terapötik deneme. J Alerji Kliniği İmmunol. 1989; 84 :753–61. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

28. Dohil M, Prendiville JS. Molluscum contagiosum’un oral simetidin ile tedavisi: 13 hastada klinik deneyim. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996; 13 :310–2. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

29. Franco I. Çocuklarda genital ve perigenital siğillerin tedavisi için oral simetidin. J Urol. 2000; 164 :1074–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

30. Scheinfeld N, Rosenberg JD, Weinberg JM. Dermatolojide Levamizol: Bir gözden geçirme. Ben J Clin Dermatol. 2004; 5 :97–104. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

31. Hogan NA, Hill HR. Levamizol ile nötrofil kemotaksisinin arttırılması ve hücresel siklik nükleotit seviyelerinin değiştirilmesi. J Enfekte Dis. 1978; 138 :437–44. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

32. Rivkin I, Rosenblatt J, Becker EL. Döngüsel AMP’nin tavşan peritoneal nötrofillerinin kemotaktik yanıt verme ve spontan motilitesindeki rolü. Nötrofil hareketinin inhibisyonu ve katekolaminler, prostaglandinler, teofilin ve kolera toksini tarafından siklik AMP seviyelerinin yükselmesi. J İmmunol. 1975; 115 :1126–34. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

33. Amer M, Tosson Z, Soliman A, Selim AG, Salem A, al-Gendy AA. Levamisol ile tedavi edilen siğil. Int J Dermatol. 1991; 30 :738–40. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

34. Saul A, Sanz R, Gomez M. Çoklu viral siğillerin levamisol ile tedavisi. Int J Dermatol. 1980; 19 :342–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

35. Schou M, Helin P. Çift kör bir çalışmada Levamisole: Siğiller üzerinde etkisi yok. Acta Derm Venereol. 1977; 57 :449–54. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

36. Cheng YC, Po HL. Verruka tedavisi için levamisol sonrası lökoensefalopati. Acta Neurol Tayvan. 2011; 20 :262–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

37. Kitamura H, Morikawa H, Kamon H, Iguchi M, Hojyo S, Fukada T, et al. Toll benzeri reseptör aracılı çinko homeostazının düzenlenmesi dendritik hücre fonksiyonunu etkiler Nat İmmünol. 2006; 7 :971–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

38. Ibs KH, Rink L. Çinko ile değiştirilmiş bağışıklık fonksiyonu. J Nutr. 2003; 133 (Ek 1):1452S–6S. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

39. Fraker PJ, King LE. Çinko eksikliği sırasında bağışıklık sisteminin yeniden programlanması. Annu Rev Nutr. 2004; 24 :277–98. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

40. Al-Gurairi FT, Al-Waiz M, Sharquie KE. Dirençli viral siğillerin tedavisinde oral çinko sülfat: Randomize, plasebo kontrollü klinik çalışma. Br J Dermatol. 2002; 146 :423–31. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

41. Sadighha A. Dirençli çoklu viral siğillerde oral çinko sülfat: Bir pilot çalışma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009; 23 :715–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

42. López-Garcia DR, Gómez-Flores M, Arce-Mendoza AY, de la Fuente-Garcia A, Ocampo-Candiani J. Yanıt vermeyen kutanöz viral siğiller için oral çinko sülfat: Gerçek olamayacak kadar iyi mi? Çift kör, randomize, plasebo kontrollü bir çalışma. Klinik Exp Dermatol. 2009; 34 :e984–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

43. Stefani M, Bottino G, Fontenelle E, Azulay DR. Çoklu ve inatçı siğillerin tedavisinde simetidin ve çinko sülfat arasındaki etkinlik karşılaştırması. Sütyen Dermatol. 2009; 84 :23–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

44. Sharquie KE, Najim RA, Farjou IB, Al-Timimi DJ. Kutanöz leishmaniasis tedavisinde oral çinko sülfat. Klinik Exp Dermatol. 2001; 26 :21–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

45. Mahajan PM, Jadhav VH, Patki AH, Jogaikar DG, Mehta JM. Tekrarlayan eritema nodozum leprosumda oral çinko tedavisi: Klinik bir çalışma. Hintli J Lepr. 1994; 66 :51–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

46. Yang J, Pu YG, Zeng ZM, Yu ZJ, Huang N, Deng QW. Genital siğillerin tedavisi için interferon: Sistematik bir gözden geçirme. BMC Enfeksiyon Dis. 2009; 9 :156. [ Ücretsiz PMC makalesi ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

47. Dianzani F. Viral girişim ve interferon. Ric Clin Lab. 1975; 5 :196–213. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

48. Turek LP, Byrne JC, Lowy DR, Dvoretzky I, Friedman RM, Howley PM. İnterferon, sığır papilloma virüsü ile transforme edilmiş fare hücrelerinde ekstrakromozomal viral genomların ortadan kaldırılmasıyla morfolojik geri dönüşü indükler. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982; 79 :7914–8. [ Ücretsiz PMC makalesi ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

49. Borden EC, Hogan TF, Voelkel JG. Diploid ve dönüştürülmüş insan hücreleri için doğal interferon alfa ve beta’nın in vitro karşılaştırmalı antiproliferatif aktivitesi . Kanser Arş. 1982; 42 :4948–53. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

50. Einhorn N, Ling P, Strander H. İnsan kondiloma aküminatasının sistemik interferon alfa tedavisi. Acta Obstet Jinecol Scand. 1983; 62 :285–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

51. Gall SA, Hughes CE, Trofatter K. Condyloma aküminatum tedavisi için interferon. Ben J Obstet Gynecol. 1985; 153 :157–63. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

52. Zedan H, Hofny ER, İsmail SA. Cilt siğilleri için alternatif bir tedavi olarak propolis. Int J Dermatol. 2009; 48 :1246–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

53. Coeugniet E, Kuhnast R. Adjuvante immuntherapie mit verschiedenen Echinacin® -Darreichungsformen. terapi. 1986; 36 :1–19. [ Google Akademik ]

54. Cassano N, Ferrari A, Fai D, Pettinato M, Pellè S, Del Brocco L, et al. Kutanöz viral siğilleri olan hastalarda Ekinezya, metiyonin ve antioksidan/immün sistemi uyarıcı bileşikler içeren bir nutrasötik ile oral takviye. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2011; 146 :191–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

55. Venugopal SS, Murrell DF. Gelişimsel olarak gecikmiş, 31 yaşındaki beyaz bir erkekte rekombinant dört değerlikli insan papilloma virüsü aşısı (tip 6, 11, 16 ve 18) ile tedavi edilen inatçı kutanöz siğiller. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146 :475–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

56. Ali KA. İnsan papilloma virüsü aşıları ve ilgili HPV tipleri arasında çapraz koruma potansiyeli. Jinekol Onkol. 2007; 107 (Ek 1):S31–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

57. Landis MN, Lookingbill DP, Sluzevich JC. Rekombinant dört değerlikli insan papilloma virüsü aşısı ile tedavi edilen inatçı plantar siğiller. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 67 :e73–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

58. Daniel BS, Murrell DF. Dört değerlikli insan papilloma virüsü aşısı ile tedavi edilen kronik multipl verruka vulgarisin tam çözümü. JAMA Dermatol. 2013; 149 :370–2. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

59. Mulhem E, Pinelis S. Genital olmayan kutanöz siğillerin tedavisi. Aile Hekimiyim. 2011; 84 :288–93. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

60. Clifton MM, Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Kincannon J, Horn TD. İnatçı siğiller için intralezyonel kabakulak veya Candida antijenleri kullanan immünoterapi . Pediatr Dermatol. 2003; 20 :268–71. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

61. Chandrashekar L. Siğillerin tedavisi için lezyon içi immünoterapi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011; 77 :261–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

62. Nofal A, Nofal E. Yaygın siğillerin lezyon içi immünoterapisi: Kabakulak, kızamık ve kızamıkçık aşısı ile başarılı tedavi. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010; 24 :1166–70. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

63. Gamil H, Elgharib I, Nofal A, Abd-Elaziz T. Plantar siğillerin intralezyonel immünoterapisi: Yeni bir antijen kombinasyonu raporu. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010; 63 :40–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

64. Meena JK, Malhotra AK, Mathur DK, Mathur DC. Birden fazla kutanöz siğili olan hastalarda Mycobacterium w aşısı ile lezyon içi immünoterapi: Kontrolsüz açık çalışma. JAMA Dermatol. 2013; 149 :237–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

65. Gupta S, Malhotra AK, Verma KK, Sharma VK. Ano-genital siğillerin tedavisi için öldürülmüş Mycobacterium w aşısı ile lezyon içi immünoterapi : Açık etiketli bir pilot çalışma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2008; 22 :1089–93. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

66. Eassa BI, Abou-Bakr AM, El-Khalawany MA. Gebe kadınlarda anogenital siğillerde yeni bir immünoterapi yaklaşımı olarak PPD’nin intradermal enjeksiyonu. Dermatol Ter. 2011; 24 :137–43. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

67. Kuş S, Ergün T, Gün D, Akın Ö. Dirençli siğillerin tedavisinde lezyon içi tüberkülin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005; 19 :515–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

68. Summers P, Richards-Altmon P, Halder R. İnatçı verruca vulgaris’in insan immün yetmezlik virüsü olan bir hastada candida antijeni ile tedavisi. J İlaçlar Dermatol. 2009; 8 :268–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

69. Maronn M, Salm C, Lyon V, Galbraith S. Siğiller ve yumuşakçalar için Candida antijen immünoterapisi ile bir yıllık deneyim. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008; 25 :189–92. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

70. Phillips RC, Ruhl TS, Pfenninger JL, Garber MR. Candida antijen enjeksiyonu ile siğil tedavisi. Arch Dermatol. 2000; 136 :1274–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

71. Kim KH, Horn TD, Pharis J, Kincannon J, Jones R, O’Bryan K, ve diğ. Siğillerin tedavisi için Candida antijeninin intralezyonel enjeksiyonunun Faz 1 klinik denemesi. Arch Dermatol. 2010; 146 :1431–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

72. Majid I, İmran S. Dirençli veya tekrarlayan siğillerde intralezyonel Candida albicans antijeni ile immünoterapi: Bir çalışma. Hintli J Dermatol. 2013; 58 :360–5. [ Ücretsiz PMC makalesi ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

73. Ritter SE, Meffert J. Lezyon içi kandida antijeni kullanılarak düz siğillerin başarılı tedavisi. Arch Dermatol. 2003; 139 :541–2. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

74. Johnson SM, Roberson PK, Horn TD. Kabakulak veya Candida deri testi antijenlerinin lezyon içine enjeksiyonu: Siğiller için yeni bir immünoterapi. Arch Dermatol. 2001; 137 :451–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

75. Horn TD, Johnson SM, Helm RM, Roberson PK. Kabakulak, Candida ve Trichophyton deri testi antijenleri ile siğillerin intralezyonel immünoterapisi: Tek kör, randomize ve kontrollü bir çalışma. Arch Dermatol. 2005; 141 :589–94. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

76. King M, Johnson SM, Horn TD. Genital siğiller için lezyon içi immünoterapi. Arch Dermatol. 2005; 141 :1606–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

77. von Krogh G. Anogenital siğillerin yönetimi (condylomata acuminate) Eur J Dermatol. 2001; 11 :598–604. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

78. Friedman-Kien AE, Eron LJ, Conant M, Growdon W, Badiak H, Bradstreet PW, et al. Condylomata acuminata tedavisi için doğal interferon alfa. JAMA. 1988; 259 :533–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

79. Lozada-Nur F, Glick M, Schubert M, Silverberg I. AIDS’li hastalarda inatçı oral siğillerin tedavisi için intralezyonel interferon-alfa kullanımı: 4 vaka raporu. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2001; 92 :617–22. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

80. Santana CF, Asfora JJ, Lins LP, Lopes CA, Santos ER. Corynebacterium parvum’a karşı bağışıklığı uyarıcı etkiler, malign neoplazi taşıyıcılarına karşı etkilidir. Rev Enst Antib. 1979; 19 :137–41. [ Google Akademik ]

81. Megid J, Dias Junior JG, Aguiar DM, Nardi Júnior G, Silva WB, Ribeiro MG. Propionibacterium acnes ile papilomatose canina tratamento. Arq Bras Med Vet Zootec. 2001; 53 :574–6. [ Google Akademik ]

82. Kalis C, Gumenscheimer M, Freudenberg N, Tchaptchet S, Fejer G, Heit A, et al. Propionibacterium acnes’in immünomodülatör aktivitesinde TLR9 gereksinimi . J İmmunolol. 2005; 174 :4295–300. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

83. Sljivić VS, Watson SR. Corynebacterium parvum’un adjuvan etkisi : makrofaj aktivasyonunun T hücre bağımlılığı. J Uzm Med. 1977; 145 :45–57. [ Ücretsiz PMC makalesi ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

84. Adlam C, Scott MT. Corynebacterium parvum ve ilgili bakterilerin lenfo-retiküler uyarıcı özellikleri . J Med Microbiol. 1973; 6 :261–74. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

85. Cantrell JL, Buğday RW. Corynebacterium parvum’dan izole edilen fraksiyonların antitümör aktivitesi ve lenforetiküler stimülasyon özellikleri . Kanser Arş. 1979; 39 :3554–63. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

86. Nasser N. Yaygın siğillerin bağışıklık uyarıcı Propionium bakteri parvum ile tedavisi . Sütyen Dermatol. 2012; 87 :585–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

87. Shivakumar V, Okade R, Rajkumar V. Çoklu siğiller için otoimplantasyon tedavisi. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009; 75 :593–5. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

88. Srivastava PK, Bajaj AK. İnatçı siğiller için Autowart enjeksiyon tedavisi. Hintli J Dermatol. 2010; 55 :367–9. [ Ücretsiz PMC makalesi ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

89. Salem A, Nofal A, Hosny D. Topikal canlı Bacillus Calmette-Guerin ile çocuklarda yaygın ve uçak siğillerinin tedavisi. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013; 30 :60–3. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

90. Metawea B, El-Nashar AR, Kamel I, Kassem W, Shamloul R. Canlı basil Calmette-Guérin’in topikal olarak kondiloma aküminatada potansiyel bir terapötik modalite olarak uygulanması: Plasebo kontrollü bir çalışma. Üroloji. 2005; 65 :247–50. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

91. Böhle A, Büttner H, Jocham D. Condylomata acuminata’nın canlı basil Calmette-Guerin ile birincil tedavisi. J Urol. 2001; 165 :834–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

92. Böhle A, Doehn C, Kausch I, Jocham D. Calmette-Guerin basilinin harici uygulama ve intraüretral aşılama ile tekrarlayan penil kondiloma aküminatasının tedavisi. J Urol. 1998; 160 :394–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

93. Arndt KA, Bowers KE, Alam M, Reynolds R, Tsao S, editörler. Dermatolojik Terapötikler El Kitabı. 6. baskı Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams ve Wilkins; 2002. Siğiller; 241–51. [ Google Akademik ]

94. Leman JA, Benton EC. Siğil. Yönetim yönergeleri. Ben J Clin Dermatol. 2000; 1 :143–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

95. Hengge UR, Esser S, Schultewolter T, Behrendt C, Meyer T, Stockfleth E, et al. Yaygın siğiller ve molluscum contagiosum tedavisi için kendi kendine uygulanan topikal %5 imikimod. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 143 :1026–31. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

96. Micali G, Dall’Oglio F, Nasca MR. İnatçı subungual ve periungual kutanöz siğillerin tedavisinde imikimod %5 kreminin etkinliğinin açık etiketli bir değerlendirmesi. J Dermatol Tedavisi. 2003; 14 :233–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

97. Poochareon V, Berman B, Villa A. %5 imikimod kreması ile kasap siğillerinin başarılı tedavisi. Klinik Exp Dermatol. 2003; 28 (Ek 1):42–4. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

98. Sauder DN, Skinner RB, Fox TL, Owens ML. Farklı hasta popülasyonlarında dış genital ve perianal siğiller için etkili bir tedavi olarak topikal imikimod %5 krem. Seks İletim Dis. 2003; 30 :124–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

99. Zamiri M, Gupta G. Bir bağışıklık tepkisi değiştiricisi ile tedavi edilen plantar siğiller: İki vaka raporu. Klinik Exp Dermatol. 2003; 28 (Ek 1):45–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

100. Hesterberg U, Böhlen LM, Marka CU. İnatçı siğillerin tedavisinde imikimod: Yeni bir tedavi seçeneği mi? Praxis (Bern 1994) 2003; 92 :535–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

101. Arıcan O, Güneri F, Bilgiç K, Karaoğlu A. Dış anogenital siğillerde topikal Imiquimod %5 krem: Randomize, çift kör, plasebo kontrollü bir çalışma. J Dermatol. 2004; 31 :627–31. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

102. Buckley DA, Keane FM, Munn SE, Fuller LC, Higgins EM, Du Vivier AW. Difensipron immünoterapisi ile tedavi edilen inatçı viral siğiller. Br J Dermatol. 1999; 141 :292–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

103. Upitis JA, Krol A. İnatçı siğillerin tedavisinde difenilsiklopropenon kullanımı. J Cutan Med Surg. 2002; 6 :214–7. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

104. Rampen FH, Steijlen PM. Dirençli palmoplantar ve periungual siğillerin tedavisinde difensipron: Açık bir çalışma. Dermatoloji. 1996; 193 :236–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

105. Hara Y. Çay kateşinlerinin sindirim sistemi üzerindeki etkisi. J Hücre Biyokimya Desteği 1997; 27 :52–8. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

106. Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Bolwell PG, Bramley PM, Pridham JB. Bitki kaynaklı polifenolik flavonoidlerin nispi antioksidan aktiviteleri. Serbest Radik Çöz. 1995; 22 :375–83. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

107. Tomita I, Sano M, Watanabe J, Miura S, Tomita T, Yoshino K ve ark. Güçlü antioksidanlar olarak çay ve bileşenleri. İçinde: Cutler RG, Packer L, Bertram J, Mori A, editörler. Oksidatif Stres ve Yaşlanma. 1. baskı Basel: Birkhauser Verlag; 1995. sayfa 355–65. [ Google Akademik ]

108. Rösl F, Das BC, Lengert M, Geletneky K, zur Hausen H. AP-1 transkripsiyon kompleksinin antioksidan kaynaklı değişiklikleri, insan papillomavirüs transkripsiyonunun seçici bir şekilde bastırılmasıyla paraleldir. J Virol. 1997; 71 :362–70. [ Ücretsiz PMC makalesi ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

109. Mukoyama A, Ushijima H, Nishimura S, Koike H, Toda M, Hara Y, et al. Çay özleri ile rotavirüs ve enterovirüs enfeksiyonlarının inhibisyonu. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1991; 44 :181–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

110. Ahmad N, Chen P, Muhtar H. Yeşil çay polifenol epigallokateşin-3-gallat ile hücre döngüsü düzensizliği. Biochem Biophys Res Kom. 2000; 275 :328–34. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

111. Li HC, Yashiki S, Sonoda J, Lou H, Ghosh SK, Byrnes JJ, et al. Yeşil çay polifenolleri, yetişkin T hücreli lösemi hastalarının periferik kan T lenfositlerinde in vitro apoptozu indükler. Jpn J Kanser Arş. 2000; 91 :34–40. [ Ücretsiz PMC makalesi ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

112. Yang GY, Liao J, Kim K, Yurkow EJ, Yang CS. Çay polifenolleri ile insan kanser hücre hatlarında büyümenin inhibisyonu ve apoptozun indüklenmesi. Karsinojenez. 1998; 19 :611–6. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

113. Stockfleth E, Beti H, Orasan R, Grigorian F, Mescheder A, Tawfik H, et al. Dış genital ve perianal siğillerin tedavisinde topikal Polifenon E: Randomize kontrollü bir çalışma. Br J Dermatol. 2008; 158 :1329–38. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

114. ABD Gıda ve İlaç İdaresi, İlaç Değerlendirme ve Araştırma Merkezi. Onay mektubu VeregenTM Merhem, %15, NDA 021902. ABD Gıda ve İlaç İdaresi, Washington, DC. 2006. [En son 3 Ocak 2010’da erişildi]. Şu adresten erişilebilir: http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/appletter/2006/021902s000ltr.pdf .

115. Gross G, Meyer KG, Pres H, Thielert C, Tawfik H, Mescheder A. İki ilacın klinik etkinliğini araştırmak için randomize, çift kör, dört kollu paralel grup, plasebo kontrollü, faz II/III çalışması Dış genital siğillerin tedavisinde Polifenon E’nin galenik formülasyonları. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007; 21 :1404–12. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

116. Beutner KR, Wiley DJ, Douglas JM, Tyring SK, Fife K, Trofatter K, et al. Genital siğiller ve tedavisi. Klinik Enfeksiyon Dis. 1999; 28 (Ek 1):S37–56. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

117. Kodner CM, Nasraty S. Genital siğillerin yönetimi. Aile Hekimiyim. 2004; 70 :2335–42. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

118. Domínguez Gómez J, Simón RD, Abreu Daniel A, Zelenkova H. Aniogenital siğilleri tedavi etmek için glisirizik asit (glizigen) ve bir immünostimulantın (viusid) etkinliği. ISRN Dermatol 2012. 2012 863692. [ PMC ücretsiz makale ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

119. Dasher DA, Burkhart CN, Morrell DS. Çocukluk siğilleri için immünoterapi. Çocuk Ann. 2009; 38 :373–9. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

120. Brandt HR, Fernandes JD, Patriota RC, Criado PR, Belda Junior W. Çocuklukta insan papilloma virüsünün imikimod %5 kremle tedavisi. Sütyen Dermatol. 2009; 85 :549–53. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]

121. Weisshaar E, Neumann HJ, Gollnick H. Kontakt immünoterapi ile yayılmış yüz siğillerinin başarılı tedavisi. Eur J Dermatol. 1998; 8 :488–91. [ PubMed ] [ Google Akademik ]